Software 2.0 and Programming ML Systems

Alex Ratner and Chris Ré

Dec 05, 2018

Recent advances in techniques and infrastructure have led to a flurry of excitement about the capabilities of machine learning (ML), leading some to call it a new “Software 2.0” [1,2]. At the core of this excitement is a breed of new (mostly deep learning) models that learn their own features from data, leading to qualitative leaps in performance on traditionally challenging benchmark tasks. However, a separate and arguably more transformative aspect of these Software 2.0 approaches is how they fundamentally change the way that developers build and program ML-driven software.

In application domains where developers traditionally spent their days coding up heuristic rules, or hand-crafting features for a model, developers now increasingly work on creating and managing training data for large black-box models that learn their own features from data, or on reusing and combining models to amortize training data costs. This shift in effort has many of its own pain points, but offers the potential for simpler, more accessible, and more flexible ways of developing software. For example, Google reportedly reduced one of its translation code bases from 500 thousand to ~500 lines of code [3], and it has become commonplace for individuals and organizations alike to quickly spin up high-performing machine learning-based applications where years of effort might have once been required.

Though there are many challenges to be solved, this new approach to building software is already changing every aspect of how developers operate and where they spend their time, while leading to real advances in the simplicity, flexibility, and speed of software development.

# The Emergence of Training Data Engineering

In application domains where ML has begun to make the biggest impact—for example, those involving unstructured data like text or images—there has been a demonstrable shift in what ML developers do with their time. Pre-ML, developers might have used sprawling repositories of heuristic code; or, several years ago, devoted entire PhDs and research careers to crafting the features for a specific ML model. Today, however, developers can often apply a state-of-the-art machine learning model to their problems with just a few lines of code, for example using commoditized model architectures and open-source software like TensorFlow and PyTorch.

Of course, there is no completely free lunch: these models are increasingly performant out of the box, but in turn require massive labeled training sets. This has led to developers shifting their time towards creating and managing training sets. Increasingly, this training data engineering is a central development activity which is done in higher-level, more programmatic ways, and can be seen as an entirely new way of programming the new ML stack. Emerging techniques include:

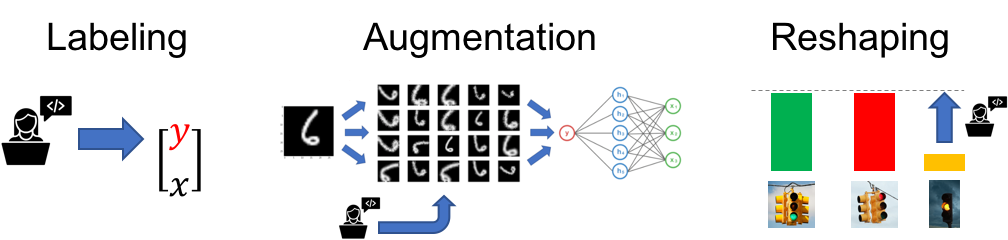

- Labeling data in higher-level, programmatic, and/or noisier ways (often called weak supervision), such as using heuristics, patterns, existing datasets and models, or crowd labelers to label training data;

- Augmenting datasets by creating transformed copies of labeled data points, thereby expressing data invariances (e.g. rotational or shift symmetries in images) in a simple, model-agnostic fashion;

- Reshaping datasets, e.g. to emphasize performance critical subsets.

Fig. 1: The emerging development activity of training data engineering, which includes labeling datasets (left), often in higher-level or programmatic ways; augmenting datasets, i.e. creating transformed copies of labeled data points (center); and reshaping datasets, for example to boost performance-critical subsets (right).

Complementary activities include a renewed focus on how to reuse pre-trained models and existing training sets, and how to amortize labeling costs across multiple related tasks. These approaches, traditionally referred to as transfer and multi-task learning, respectively, have attracted renewed interest given the modularity, composability, and infrastructural support of modern ML models.

# Technical Perspective: Flipping the Old ML on its Head

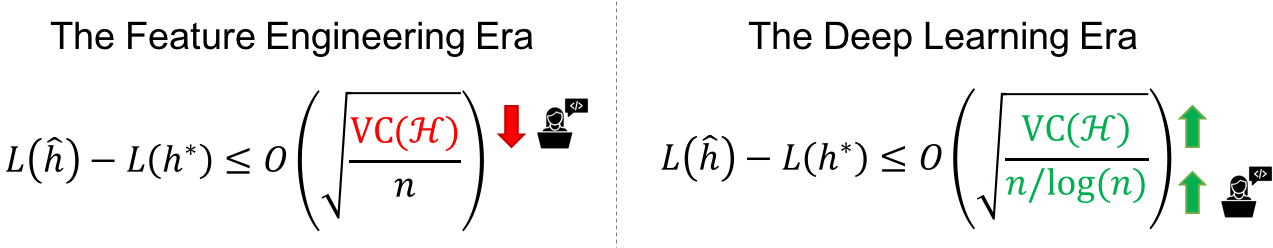

One perspective on the shift in machine learning that this new training data-driven approach represents can be found through the lens of machine learning theory. Specifically, we consider a standard type of uniform convergence result which has informed much of the ML practitioner’s doctrine over the last few decades. While misleading if taken as too literal of a guide—and potentially lacking explanatory power in the context of today’s deep, over-parameterized model classes [5]—it serves as a simple framework for intuition here.

Let H be the (possibly infinite) hypothesis class—i.e. a set of possible models / model parameters, one of which we need to select—let VC(H) be the VC dimension of the model class—a classic measure of how complex it is—and let n be the number of i.i.d. labeled training points. We then consider bounding the generalization error, i.e. the difference in expected error between a model we empirically select, ˆh, and the optimal model h∗, as a proxy for good test time model performance. We can then compute a standard result (see e.g. [4] for proof and details) stating that generalization error is upper-bounded by O(√VC(H)log(n)n).

In the old pre-deep learning way of approaching ML development, the majority of development time was usually spent on engineering the features of a model. Features are easy to think of (e.g. for images: any indicator for a specific combination of pixels could be a feature); a small set of good features is the tricky thing. Thus, these feature engineering-driven approaches could be viewed as an effort to craft a small model class to be learned on a small hand-labeled dataset. Instead, the current approaches flip this paradigm on its head: developers focus on generating large labeled datasets to support large, complex model classes like deep neural networks.

# Research Directions

These new approaches represent a fundamental shift in how machine learning-driven software is built, affecting every aspect of what developers focus and spend time on. While many challenges remain, this new “Software 2.0” way of interacting with ML seems to hold the promise of being a fundamentally more accessible and powerful way of programming ML-driven systems. The ensuing research questions of why, when, and how this new way of building ML-driven software can be most effective are what we are most excited about right now:

- How can we enable users to label training datasets in higher-level, faster, and more flexible ways? Our Snorkel framework is one initial answer to this: instead of hand-labeling training data, users write labeling functions to programmatically label it, which Snorkel then models and combines.

- How can we enable users to reshape, manage, and debug training sets? For example, to emphasize certain “slices” of data that are mission critical and/or sources of model errors.

- How can we build systems and algorithms to support transfer and multi-task learning over tens to hundreds of tasks, as people more rapidly create new training sets for related tasks, e.g. using fast weak supervision approaches like Snorkel? (For some initial work here, see our upcoming AAAI'19 paper)

- When can we expect these training data-driven techniques to be most beneficial? For example, from a theoretical perspective, when should programmatic training data labeling or data augmentation be helpful?

# References

- https://medium.com/@karpathy/software-2-0-a64152b37c35

- https://petewarden.com/2017/11/13/deep-learning-is-eating-software/

- https://twimlai.com/twiml-talk-124-systems-software-machine-learning-scale-jeff-dean/

- https://web.stanford.edu/class/cs229t/2015/notes.pdf

- https://openreview.net/forum?id=Sy8gdB9xx